Mental Health Toolkit

Welcome to the Kentucky Office for Refugees Mental Health Toolkit

This resource is intended for anyone interested in supporting the mental health and emotional well-being of families who have been resettled through the refugee program. Please scroll down and follow the links for all resources available.

For edits and resource updates please contact Health Promotion Coordinator Jennifer Ballard-Kang at jballardkang@archlou.org.

There is a great need for care providers in all areas to serve refugee families and English language learners successfully, particularly in mental health. Care providers face many challenges in support of meeting the needs of refugees. This page is designed to provide information and tools on serving refugee families appropriately.

To learn about the refugee resettlement process in the United States start here.

To learn about refugee resettlement in Kentucky start here.

For an introduction to refugee mental health, research and resources visit The National Child Traumatic Stress Network website.

To review the 2019 Refugee Mental Health presentation, click here.

To review the Kentucky Statewide Mental Health Needs Assessment Key Findings Report dated June 30, 2023, click here.

To review the Kentucky Statewide Mental Health Needs Assessment Provider Perspective Technical Report dated June 30, 2023, click here.

Kentucky Refugee Mental Health Providers

Mental Health Emergencies

Centerstone Crisis Hotline adults 502-589-4313 + children 502-589-8070

U of L Health Peace Hospital and 502-451-3333 (formerly Our Lady of Peace) Emergency psychiatric

U of L emergency room 562-4680

Mental Health Providers

Survivors of Torture Services Family Health Centers Americana- therapy and case management (to find out if someone qualifies please call) Phone: 502-772-8891 Fax: 502-363-8616

Centerstone Intake line: 589-1100 (please have ss#, address and medicaid # ready)

University of Louisville Peace Hospital IOP + partial inpatient program 502-451-3330

New Hope International Adult, English/Kinyarwanda/Swahili/French/many DRC dialects 502-650-3804

Mindful Direction Adult + child (English/Amharic/Tigrinya) 502-653-7439

Kentucky Counseling Center Adult and child, in-office/in-home 502-252-1865

Mental Health Emergencies:

Eastern State Hospital 1350 Bull Lea Rd Lexington, KY 40511 859-246-8000

University of Kentucky ER/Good Samaritan Psych 310 South Limestone Lexington, KY 40508 859-226-7000

Mental Health Providers:

Bluegrass Community Health Center 1306 Versailles Rd & 151 N Eagle Creek Lexington, KY 859-259-2635

Healthfirst Bluegrass 496 Southland Dr & 1640 Bryan Station Rd #1 859-288-2425

KVC Health Systems (Children Only) 859-254-1035

NewVista 1351 Newtown Pike 1-800-928-8000

Mental Health Providers

KY Steps Behavioral Health Services – 2815 Russellville Rd.Bowling Green, KY 42101 270-938-1020

Life Skills – 380 Suwannee Trail Street Bowling Green, KY 42103 270- 901-5000

Owensboro Health For referrals call 270-417-3744

Trainings + Information

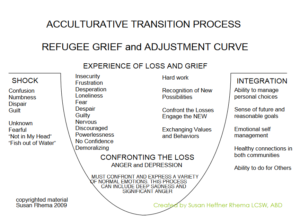

Refugees often experience what is called the “adjustment curve” when migrating to a new place away from their mother land. While not every person is the same, many resettled families may have this general experience, or some of the symptoms related to each stage.

A Power Point presentation overview on Refugee Mental Health can be found here.

Refugee Backgrounders– The Cultural Orientation Resource Center has produced numerous publications providing key information about various refugee populations. These Refugee Backgrounders and Culture Profiles include a population’s history, culture, religion, language, education, and resettlement needs, and brief demographic information. To learn more about specific refugee cultures and countries of origin, visit the Cultural Orientation Resource Center here.

You can view our YouTube video on Cultural Competency here.

Trauma-Informed Care: What it is, and Why it is Important.

Click on icthe ons below for helpful links.

View a YouTube video of mental health practitioners informally discussing the application and meaning of trauma informed care here.

Healing Encounters–

Refugee Mental Health- A Power Point slide introduction on the main experiences and mental health challenges many refugees may face can be found here.

Stories of Hope from Bhutanese Refugees

Trauma Informed Care

MODEL FOR SUICIDE ASSESSMENT AND TREATMENT: A TRAUMA INFORMED APPROACH

Created by Susan Heffner Rhema, PhD, LCSW

With special thanks for the contribution by Laura Frey, PhD University of Louisville

INTRODUCTION

Traditional approaches to suicidal ideation with clients have been to immediately shift away from the treatment plan into an assessment process that creates a distinct break in the therapeutic process. This shift in focus by the provider decreases trust. Research indicates that a marked shift in approach and documentation reduces the client’s capacity to feel safe, reduces honest sharing of the suicidal thoughts, and reduces the potential impact of treatment.

Viewing the suicide ideation response through a trauma informed lens helps us to respond to client’s thoughts and needs in the moment as well as assess the critical information necessary to ensure client safety. This document provides a guide to responding with both the critical assessment of client safety as well as enhancing the continued client engagement and supportive services, after the disclosure of suicide ideation.

Working primarily with refugees, including survivors of torture, this model was developed in response to the lack of a model that fit use with this population. Following a lecture by Dr. Frey, the following model was adapted with the addition of scripted language to reinforce the elements of trauma informed practice by Dr. Susan Rhema.

Overview

The initial response by the provider to a client disclosure of suicidal ideation or morbid rumination is to focus on encouraging the client to express their feelings and thoughts, and then to follow with an exploration of the related behavior and includes:

- Integrated Assessment approach, (Respond vs. React)

- No “Contract”, RATHER a Commitment to Treatment

- Recognition of category of Morbid Rumination as not Suicidal Ideation.

- Focus on building connection and supporting treatment rather than limiting liability

Quotes From Survivors

Quotes taken from Participants of: Live Through This

“I have one therapist who is trustworthy. She has understood the gradations of risk with self injury and considering suicide. This makes me more likely to be honest with her and ask her for help when I need it.”

“I was thinking about this last night and was struck by the fact that as many times as I have been asked if I was feeling suicidal or thinking about suicide—and there have been dozens of times—no one has ever asked me how it felt, which is strangely odd in a field where every other question is ‘And how did that make you feel?’”

THE MODEL

Categorizing Suicide Ideation

Morbid Rumination

Thoughts about death, dying, or not being alive: “Everything would be easier if I were dead.”, “I want to just disappear.”

It may be noted that survivors of torture may be more likely than some other populations to express morbid rumination, rather than true suicidal ideation. NOTE: morbid rumination is NOT considered a category of suicidal ideation.

Wish to Die

Thoughts about a desire to be dead or not alive anymore, or a wish to fall asleep and not wake up:

- “I think about stepping off the curb in front of a truck.”,

- “I cannot live like this anymore.”

Active Ideation

Thoughts of wanting to end one’s life, with various levels of intent and planning:

- “I think about buying a gun and ending it.”,

- “I am saving up my medication until the time is right.”

INTENT PLAN

Subjective (expressed) Method

Objective (observed by others) Time and Place

Preparatory acts or behavior

Acts or preparations towards making a suicide attempt (anything beyond verbalization or thought):

- “I gave all my baseball cards to my brother.”

Categorizing Previous Attempts

Aborted Attempt

When individuals begin to take steps toward making an attempt, but stop themselves before they actually have engaged in an attempt

Interrupted Attempt

When an attempt is interrupted by an outside circumstance from starting the potentially self-injurious act

Suicide Attempt

A nonfatal, self-injurious act with at least some intent to die

Death by Suicide

Death from injury where there is evidence it was self-inflicted and that there was at least some intent to die

Expanded from: Mann, J., & Oquendo, M. (2003). The Columbia Suicide History Form. New York: New York State Psychiatric Institute

Determining Risk (Acute Or Chronic)

Acute factors = all things that fluctuate in severity and will alleviate to some degree as the suicidal crisis resolves

Warrants immediate clinical attention, possible hospitalization

Nature of Thinking, Intent, Symptoms

Chronic factors = static factors related to the patient’s susceptibility to becoming suicidal in the first place

Warrants long-term outpatient care

Survivors of multiple attempts typically have chronic risk

Cognitive susceptibility, Biological susceptibility, behavioral susceptibility

Reference: Rudd, M. D. (2006). The assessment and management of suicidality. Sarasota, FL: Professional Resource Press

Preparation

It is essential that providers consider their own feelings about suicide. Our previous experiences with the topic, whether professional or personal, has an impact on how we respond to a client. In preparation, a provider is best suited to consider their own feelings, experiences, previous responses and bias’s.

Here are a few questions to consider:

- Why do people kill themselves?

- Is it ever acceptable to die by suicide?

- Can suicide be prevented?

- Is suicide always preventable?

- Is someone at fault when someone completes the act of suicide?

- Do people who access care want to die?

- What are your individual professional responsibilities with a suicidal patient?

These were derived from Rudd, M. D. (2006). The assessment and management of suicidality. Sarasota, FL: Professional Resource Press.

It is recommended that a provider explore your responses to these questions before offering clinical care or assessments. Your professional obligations should drive your behavior with suicidal clients, not your personal beliefs or related emotion.

Guide to the Assessment

The following guide is derived from, Reference: Rudd, M. D. (2006). The assessment and management of suicidality. Sarasota, FL: Professional Resource Press.

- Conceptualize the therapeutic relationship and alliance as part of assessment and management process.

- Use clear, unambiguous language.

- Maintain good eye contact when asking difficult questions.

- When needed, provide historical and developmental context for the current therapeutic relationship.

- When the opportunity emerges, ask specific questions about problems the patient has had during previous disclosures.

- Make the therapeutic relationship a routine and consistent item on the treatment agenda.

- Use the established relationship as a basis for connecting in a deeper manner.

- Stay focused on the client when you ask difficult questions.

- Talk with the client about how they felt, or were treated after previous disclosures.

- Talk with client about how this disclosure can be different and more effective.

The following are examples of responses that may be used at the time of disclosure:

- How did you feel as you told me about the suicidal thoughts?

- I am glad you feel you can be honest with me about these thoughts. How are you feeling now?

- How did you feel last night when you were thinking about hurting yourself?

- What are you thinking about yourself when you are considering suicide?

- What event occurred just prior to this most recent period of considering (planning) suicide?

Completing the Assessment, Response, and Documentation

Begin by RESPONDing with the person rather than REACTing to the information.

You said that you are “ restate the client’s words here”, and I want to understand what you are thinking and feeling. Please tell me what you are feeling when you think this about yourself.”

ENGAGE the discussion

Can you tell me (exactly) what you have been thinking about hurting yourself?

When do you most think about this?

In the past week, how often have you thought about this?

How do you feel in the moment that you are considering this?

What circumstances most often lead you to considering suicide?

A moment ago you said “ restate the client’s words”, and I would like to know more. Please tell me what you are thinking/feeling when you said this.

What feeling(s) did you have at the moment when you said, “restate the client’s words”?

What were you thinking at the moment when you said, “restate the client’s words”?

How did you feel as you told me about the suicidal thoughts?

I am glad you feel you can be honest with me about these thoughts. How are you

feeling now?

How did you feel last night when you were thinking about killing yourself?

What are you thinking about yourself when you are considering suicide?

What event occurred just prior to this most recent period of considering (planning) suicide?

CATEGORIZE the thoughts

If response fits the category of Morbid Rumination then:

Respond with support, Continue to explore feelings, Explore feelings of loss, Symptoms of depression, Review activities, Support Strengths and resources

If the response fits “Wish to die” or any category beyond (Suicidal Ideation) you should compete a Columbia Suicide Severity Ranking Scale form.

Respond by asking:

Can you tell me how you have been thinking about killing yourself?

Document detail with direct quote.

IDENTIFY current thinking

Please tell me more (detail) about the suicidal thoughts that you told me about today. Identify self-beliefs, triggers, challenges, strengths and coping resources.

When did you think about (…..use client’s own words….?)

What happened just before you thought about this?

What has kept you from killing yourself?

EXPLORE and DOCUMENT Suicidal History

- Precipitant – What triggered the crisis? What happened just before?

- Nature of Ideation/Attempt – What were you thinking at the time?

- Plan/Intent- What did you do and what happened?

- Outcome- Were you injured? Did you receive medical care? Or, Follow-up treatment? To whom did you disclose?

- Reaction – What was your reaction to surviving? To the treatment you received?

- Subjective/Objective – Lethality? What were the reactions of others? How did people react to your attempt? How did people respond when you talked about killing yourself?

ASSESS

Specificity

Thinking – Frequency, intensity, and duration of thoughts

Planning – When, where, and access to means

Please tell me how often you have thought about _____ in the past few days. Where would you _______?

Intent

Important to assess both objective and subjective intent

Ask about desire, preparations, and rehearsing

Have you prepared the _____to kill yourself? Did you practice how you would do it?

Protective Factors IMPORTANT

Most important are social support and active treatment relationship

Who is available and accessible during periods of crisis?

When do you most think about ____? Who, when you think of them, keeps you from ____? Where/When are you most/least likely to _____

GATHER Information, and

DOCUMENT Everything in Detail

- Acute factors = all things that fluctuate in severity and will alleviate to some degree as the suicidal crisis resolves

- Chronic factors = static factors related to the patient’s susceptibility to becoming suicidal in the first place

It is important to document both acute and chronic risk factors. For survivors of multiple attempts, chronic factors may still remain even when acute symptoms and intent have subsided.

Establishing Risk Level

| Acute Suicide Risk Continuum | |

| Risk Level | Description |

| Minimal | No identifiable suicidal ideation.

• client with morbid ruminations could be considered at no risk or at minimal risk. • client may fall under mild risk based on the severity of depressive symptoms. |

| Mild | Suicidal ideation of limited frequency, intensity, duration, and specificity

• No identifiable plans • No associated intent • Mild dysphoria and related symptoms • Good self-control (both objective and subjective assessment) • Few other risk factors • Identifiable protective factors, including available and accessible social support |

| Moderate | Frequent suicidal ideation with limited intensity and duration, some specificity in terms of plans, no associated intent

• Good self-control • Limited dysphoria/symptomatology • Some risk factors present • Identifiable protective factors, including available and accessible social support |

| Severe | Frequent, intense, and enduring suicidal ideation, specific plans, no subjective intent but some objective markers of intent

• Evidence of impaired self-control • Severe dysphoria/symptomatology • Multiple risk factors present • Few, if any, protective factors, particularly a lack of social support |

| Extreme | Frequent, intense, and enduring suicidal ideation, specific plans, clear subjective and objective intent

• Impaired self-control • Severe dysphoria/symptomatology • Many risk factors and no protective factors |

Moving Forward

This model is a no contract model. Traditionally a contract was “an agreement between client and clinicians in which the patients agree not to harm themselves and/or to seek help when in a suicidal state and the patient believes he or she is unable to honor the commitment” (Rudd, Mandrusiak, & Joiner, 2006). One reason cited for not using the term “contract” implies more care for liability and medicolegal aspects of practice than for patients (Miller, 1999). Another is that no standard definition for no-suicide contracts or agreement about what they should contain (Rudd, 2006). Also, the research on no-suicide contracts does not suggest that they work consistently (Jones et al., 1993; Mishara & Daigle, 1997; Kelly & Knudson, 2000)

Instead as an alternative it is recommended to use both a Commitment to Treatment (CTS) and Crisis Response Plan (CRP).

- No Contract- Evidence suggests that clients feel coerced

In it’s place, there must be TRUST and TRANSPARENCY

- Commitment to Treatment

Set Goals together to build COLLABORATION and MUTUALITY

Commitment To Treatment

Below is an example:

I, ________, agree to make a commitment to the treatment process. I understand that this means that I have agreed to be actively involved in all aspects of treatment including

- attending sessions (work together to set a realistic plan for number of sessions and what to do when I can’t make it),

- setting goals (what are new goals based on this commitment, who else should be included in setting goals, how will these be reviewed)

- voicing my opinions, thoughts, and feelings honestly and openly (discussion of who I can share this information with, and in what settings am I most comfortable to be myself)

- active engagement (what is my role in this relationship)

- completing homework assignments, (what can I do for myself to improve my situation or change my thinking)

- taking medications as prescribed,

- experimenting with new behaviors and new ways of doing things, and

- implementing my crisis response plan when needed.

I also understand and acknowledge that a positive outcome depends on the amount of energy and effort I make. If I feel this is not working, I agree to discuss it with _____________, and attempt to come to a common understanding as to what the problems are and identify potential solutions. In short, I agree to make a commitment to living. This agreement will apply for the next 3 months, at which time it will be reviewed and modified.

Signed: ___________________________________ Date: ________________

Crisis Response Plan

The following guide can help to establish a crisis response plan. When I’m acting on my suicidal thoughts by trying to find a [method with which to kill myself], I agree to take the following steps:

Step 1: Try to identify specifically what’s upsetting me

Step 2: Write out and review more reasonable responses to my suicidal thoughts, including thoughts about myself, others, and the future

Step 3: Review all the conclusions I’ve come to about these thoughts in the past in my treatment log. For example, that the events were not my fault and I don’t have anything to feel ashamed of.

Step 4: Try and do the things that help me feel better for at least 30 minutes (listening to music, going for a walk, calling my best friend)

Step 5: Repeat all of the above at least one more time.

Step 6: If the thoughts continue, get specific, and I find myself preparing to do something, I’ll call the emergency call person at ______________.

Step 7: If I still feel suicidal and don’t feel like I can control my behavior, I’ll go to the emergency room located at: _________________________.

REFERENCES

Posner, K., Brent, D., Lucas, C., Gould, M., Stanley, B., Brown, G., Fisher, P., Zelazny,J., Burke, A., oQuendo, M., Mann, J., Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale, 2009.

Mann, J., & Oquendo, M. (2003). The Columbia Suicide History Form. New York: New York State Psychiatric Institute

Rudd, M. D. (2006). The assessment and management of suicidality. Sarasota, FL: Professional Resource Press.

Rudd, Mandrusiak, & Joiner, (2006)- No contract

Form N-648 is a form used by United States Citizenship and Immigration Services and is completed by individuals going through the citizenship process if they want to seek an exemption from the English and civics testing required for US citizenship. The person requesting the exemption must have a physical or developmental disability or mental condition that is expected to last more than 12 months. This form must be certified by a licensed medical doctor before it can be submitted.

For more information click here.

Download the N-648 brochure here.

A one-hour webinar on Trauma Informed De-escalation can be found here.

Also, review the Switchboard website for a broad variety of resources and free training videos.